The Problem with “Stop Bringing Me Problems”

By: Josh

I was standing among a small huddle of senior leaders within my organization and witnessed a really interesting conversation take place. All the leaders were very experienced, serving in senior positions amongst their 700-person departments. In this huddle, they were talking casually with their boss. And what I heard in this small group of senior leaders was actually pretty perplexing. Instead of proactive, mature problem solvers, I found that they were doing nothing but identifying problems for their boss. And all this problem identification came in the form of complaining.

After a short bit of listening to this, the boss finally cut off the group with a sharp, “All you’re doing is bringing me problems. Stop bringing me problems. Give me solutions.”

I was challenged with the department deputies and their seeming inability to move beyond complaints. But I was also challenged by their boss’s response. Aren’t leaders supposed to help deal with problems? My mind goes to what former US Secretary of State, Colin Powell, said, “Leadership is solving problems. The day Soldiers stop bringing you problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help or concluded you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership.”

Who is right…or wrong…in this situation? How should leaders frame and address problems?

Framing Problems

It’s easy for leaders to frame problems negatively. Problems stifle progress, consume time and resources, are inconvenient, frustrating, and distracting from what we should be doing. For 24 years, leaders have been encouraged to stop taking and stop feeding “the monkeys.”

Leaders don’t have time, energy, or capacity for more problems. So, stop bringing us problems, right?

But leadership is about service. Service to people, to a cause, to making things better. Doesn’t that include removing barriers to enable progress and peoples’ success?

I argue that leadership is just as much a business of problems as it is one of people. The importance in accepting this argument lies in understanding how leaders frame and approach problems. So, let’s start with one way to do that.

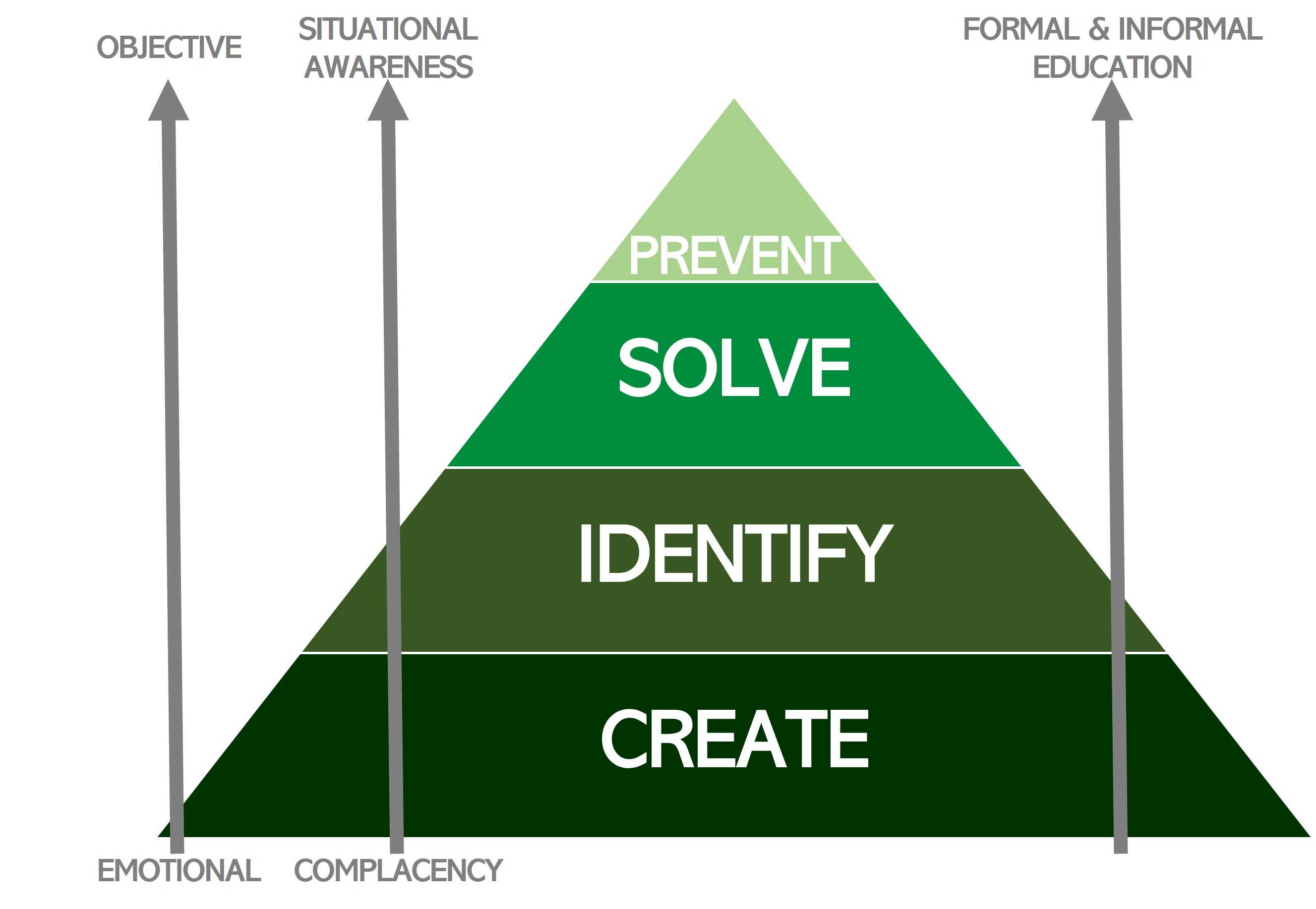

A mentor offered me this graphic a few years ago stating that there are four types of people when it comes to problems.

At the bottom are the people who CREATE problems. Their behavior is often driven by immaturity, emotions, and complacency. Not only do they not bring much value to the organization, but in fact tend to have a negative impact on the value the organization produces.

Problem creators are followed by people who IDENTIFY problems. They don’t necessarily detract from the organization’s results, but their value is limited to finding and identifying problems. For this group of problem identifiers, their actions stop there, falling short of actually adding organizational value.

There are people who take action to respond and SOLVE problems. They have the maturity, experience, and education to identify problems and then do something about it. This is the level where leaders in the organization begin to add notable and positive value to the organization.

Lastly, at the top, are people who PREVENT problems. They have the situational awareness, objectivity, education, and experience to foresee coming issues and set conditions before they become problems.

Important Takeaways from This “Problem Model”

So, what should we take away from this model? Here are five important lessons that resonate with me.

- The “sweet spot” for leaders. The graduate level of leadership is straddling the line between preventing and solving problems. Leaders are human with a limited set of experiences and education, so we will never be able to prevent everything. But what we can’t prevent, we solve. Leaders are proactive. We don’t have to wait for instruction to add value. I often resort to a quote from Clay Scroggins, author of How to Lead When You’re Not in Charge, saying, “I have some influence with people, I have a network of colleagues, and a sense of what needs to be done; I don’t need to wait to be told what to do.”

- Identifying problems = complaining. The problem identifiers may add value by shedding light on an unknown issue, sure. But that’s because they are in the habit of doing it. Everything to problem identifiers is a problem, an inconvenience, or falling short of the mark. It’s easy to complain. Stopping at identifying the problem absolves people of the responsibility to do something about it. “Oh, this isn’t my problem, that’s their” Complaining does not add value.

- Sometimes, however, leaders do need to identify problems. Leaders make people and organizations better. To get better, we need to first acknowledge there is a problem. So, leaders often have to help people identify and understand problems. Unlike problem identifiers though, leaders take the critical next step up the model to solve the problem with, for, and through their people.

- The problem with “don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions.” We’ve concluded that leadership is a business of problems. We can never rid ourselves of them, nor prevent people from bringing them to us. The higher up a leader is in an organization, the more resources we have at our disposal. Higher levels solve harder problems for their subordinate echelons. As leaders, we should absolutely welcome problems.

- But don’t bring me just problems. We welcome problems, yes, but we don’t absolve our people of addressing them themselves. As leaders, our approach to people seeking our support with problems should communicate, “bring me a problem you can’t solve, show me what you’ve tried so far, and recommend possible options to move forward with.” There is a lot of power in simply asking, “What do you recommend?”

How Do We Deal with Problems?

So, if we should welcome problems, how do we deal with them?

I think this is a two-part answer, with each part dependent on your role in the organization. The first is for the junior member bringing a problem to our boss. The second is for when we are the leader to whom people are bringing the problem.

If we are the junior member with the problem, we must identify and also analyze the problem. What are the contributing factors, root causes, impacts, and the significance of the situation? We have a responsibility to do the analysis for our boss and present it clearly. We also should generate possible future options, each one with assessed risk and opportunities. Finally, we ought to make a recommendation for what action to take and why. This type of in-depth approach demonstrates professional maturity, helps our leader to fully understand the problem (as much as possible), and enables them to support us and take action.

Now, as leaders on the receiving end of problems, we should help our people through a deliberate problem-solving process. Remember, we should not absolve them of the responsibility of dealing with the problem, but we provide support through resources, guidance, and decision-making. Over time and practice, an approach like this helps team members become more self-sufficient, confident in their abilities, and capable of addressing bigger problems on their own in the future.

Supporting people through a problem-solving process can look like helping them:

- Frame the problem: Ask five whys. “Hey boss, we’ve got problem X.” Why’s that? “Well, company A won’t comply with requirement 1.” Hmm, why? “Because they say they don’t have the resources necessary to meet those requirements.” What kind of resources are they missing? “So, we got a list of things they need, which includes…” Are we able to help with those? “Yes, but we will need the manager of department Z to sign off on them.” Ah, yes, I can certainly help with that. By asking a series of clarifying questions, a version of five whys, we can get to the root issues at play to know how we can actually help. Just by looking at the simple example above, we can see that the problem initially framed as a non-compliance issue was in fact a request for authorization to allocate resources issue. So, start by helping people frame the problem.

- Analyze it: What can we control? What can’t we? Who is responsible? What are our time and resource restrictions? What are our facts, assumptions, restrictions, and limitations? The more we help our boss to fully understand the problem, the more able (and willing) they’ll be to support.

- Generate options: This will require some creative and critical thinking. Generate options, as many as you can, even seemingly simple or outlandish ones. Seek a diverse pool of input. Help your people think through the risks and opportunities of each option, too, to do a litmus test on those that are feasible vs. those that are not.

- Select a solution: What are the criteria needed to select one of the viable options? Whose responsibility is it to select? Can we push that authority down? Have we mitigated as much risk as possible? Developing clear decision authority, as well as selection criteria for a “best fit” solution, enables and empowers us to firmly occupy the “Problem Solver” domain in our model.

- Implement: Follow through, get updates, and hold people accountable for putting the solution into action.

Think about the last time you faced a major problem in your organization and how you handled it. Were you a problem identifier or a problem solver? Maybe your entire team faced a challenging situation and you stumbled to get past it? How can the model offered above help you better handle a similar situation in the future?

Remember, leadership will always be a problem-saturated business. As you consider this model and the ways you might implement it, I encourage you to reflect on a few questions.

First, do our words and behaviors unintentionally communicate, “don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions?”

Second, are we problem identifiers, solvers, or preventers? What do we need to be in this moment or season of our team’s work?

Lastly, how can we best support our people through their next problem, using this as an opportunity for development?

It might also be beneficial to share this model and these questions with our teammates to initiate productive conversations on how we collectively frame and approach problems as a team.